No time for reading the story? Give it a listen on Spotify.

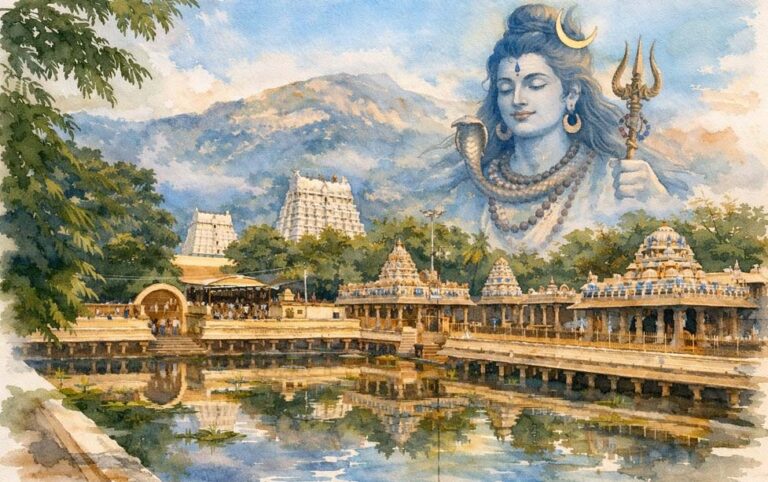

Lord Shiva awakens the cosmos with the primal sound of Nāda, giving birth to Sanskrit through his divine dance and the beat of his damaru.

Characters in the story:

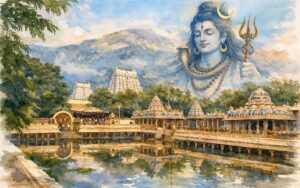

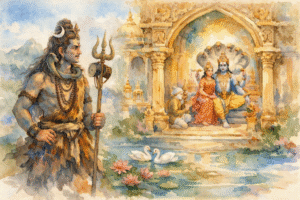

Lord Shiva: Lord Shiva, a major deity in Hinduism, is revered as the destroyer of evil and the force of cosmic change. He is depicted as a meditative ascetic or a divine dancer, characterized by his third eye, a serpent around his neck, and a trident in his hand.

![]()

Rishi Panini: Rishi Panini was a renowned ancient Indian Sanskrit grammarian, best known for his comprehensive and scientific analysis of Sanskrit phonetics, phonology, and morphology. His seminal work, the Ashtadhyayi (Eight Chapters), is a concise yet detailed treatise on Sanskrit grammar and is considered a cornerstone of linguistic studies.

In the beginning, before the stars had names, before wind had direction, before speech had syllables—there was only stillness. The universe lay curled within the heart of Mahadeva, the Great God Shiva, who meditated in perfect silence atop Mount Kailasha.

There was no light, no darkness, no movement—only the subtle throb of potential. Then, from within his silent trance, a pulse emerged—a subtle vibration, neither sound nor silence.

It was Nāda—the primal, eternal sound.

From this Nāda, there arose a resonance that spiraled into form. The first sound echoed across the void: “AUM”

The sound was not heard—it was felt. It did not travel through space—it created space. It was not spoken—it was Being.

The Dance of Creation

As the Nāda expanded, Shiva opened his third eye and began to move. With every gesture of his cosmic dance—the Tāṇḍava—a new vibration emerged:

From his right foot came the syllable “a”,

From his left foot, the syllable “u”,

And from his hands, the syllable “m”.

Thus was born AUM, the seed of all language, the essence of all Vedas, and the soul of Sanskrit.

Manifestation of Sanskrit

From Shiva’s damaru (drum) burst forth fourteen Mahāśabdas (great sounds)—the Maheshwara Sutras—each carrying within it the seeds of phonetics, grammar, and meaning.

As the damaru pulsated, the universe responded:

Sounds formed syllables,

Syllables became mantras,

Mantras gave rise to the Vedas,

And the Vedas crystallized into Sanskrit.

The gods listened in awe. Brahma, the Creator, took these sounds and composed the Vedas. Saraswati, the goddess of wisdom, wove them into patterns of poetry, philosophy, and song. The rishis received these vibrations in their meditations and sang them into the fabric of the world.

Knowledge Through Sound

In a sacred cave, Rishi Panini meditated upon Lord Shiva. As he reached the stillness of his breath, he heard the fourteen sounds of the damaru and, inspired, wrote the rules of Sanskrit grammar—the Ashtadhyayi—preserving the divine language in human form.

Even today, when sages chant Vedic mantras, they say:

“Shabda Brahman iti Shivaḥ”—Sound is Brahman, and Brahman is Shiva.

For in every syllable of Sanskrit, in every vibration of sacred chant, one can still hear the echo of Shiva’s damaru—the heartbeat of creation.

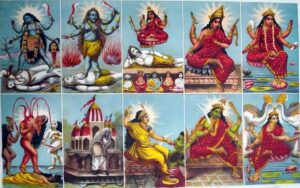

![]()

Author’s note: This story is rooted in the Shiva Purana, which attributes the origin of Sanskrit to Lord Shiva through the concept of Nāda—the primal sound from which all creation emerges. In this tradition, Shiva is seen as the source of sacred vibration, and Sanskrit is viewed as a divine language born from his cosmic dance and the beat of his damaru. However, other Puranas offer alternate perspectives: the Vishnu Purana describes the Vedas and Sanskrit as emerging from Lord Vishnu’s breath, while the Devi Purana and other texts associate the creation of speech and language with Goddess Saraswati, the embodiment of wisdom and Vāk (divine speech). These varying accounts reflect the pluralistic and symbolic nature of Puranic storytelling, where different deities are venerated as the origin of universal truths through their own cosmic roles.

![]()

Thus, every syllable of Sanskrit carries the rhythm of Shiva’s cosmic dance and the essence of eternal truth. To speak it is not merely to communicate—but to echo the voice of creation itself.